I am one of many Native employees here at OOHS with a close connection to the impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system Some may think this history is in the distant past but, for my family and other Native families, we are not far removed from the trauma - and the healing - that continues throughout our communities.

I am one of many Native employees here at OOHS with a close connection to the impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system Some may think this history is in the distant past but, for my family and other Native families, we are not far removed from the trauma - and the healing - that continues throughout our communities.

Over the years I have heard many stories about the boarding school on my Indian Reservation, St. Mary's Mission. I am an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation. St. Mary's was the school all my aunties and uncles attended. It is also the same Mission my great-grandmother, my grandmother, and her siblings attended.

When I was young, everyone in the community called it "The Mission." The Mission held Catholic Church services and various community events, including funerals. The funerals are what I remember best. Most of my ancestors are buried at The Mission's cemetery on the hill. The first funeral I remember attending was my great-grandfather's His service was a combination Native traditional ceremony and a full Catholic Mass. Even though I was young, I remember reciting the Lord's Prayer and singing our traditional prayer songs.

Years later I realized that my great grandpa's funeral was so memorable because the traditional elements stood out. The funerals I attended before were Catholic services led by a White priest where parishioners held beaded rosaries and took communion. That all happened at my great grandpa's funeral too, but I distinctly remember his casket being taken to the cemetery for the Tribal cultural services. At the funeral, a Tribal elder led us in traditional song, prayer and culminated with my great grandpa's burial. But what struck me was the traditional part of the service seemed very short.

The combination of these two cultural practices can be directly tied to generations of people from my reservation forced to attend boarding school at St. Mary's Mission. Family and friends were made to learn Catholic prayer, follow the church's strict belief system, and kept from speaking our Tribal language or holding any cultural ceremonies.

It felt uncomfortable to look around a memorial service during the Catholic portion and realize nearly everyone in my family had attended The Mission. Younger people in our Tribe always questioned why we still followed Catholic practices. In our Tribal culture, it is a show of respect for our Elders.

My aunties would tell us stories about what happened to them at the school. Physical abuse, sexual victimization and corporal punishment was not just the norm, it was the expectation The long-term effects on the generations of families who attended St. Mary's Mission are widely known on my reservation. Small things like hugging and showing love has always been missing. People drink to hide the trauma of attending the school, parents don't know how to show their affection as they received none at The Mission, and elders are re-learning ceremonial practices and our language because that was all taken away.

My aunty once told me when she was in the fourth and fifth grade dorms, the children knew which priests liked little boys and which priests liked little girls. The children pushed their beds together, tying each other together with their shoelaces so if a priest came to take a child in the middle of the night, the activity would wake up lots of children in the dorm. The hope being that the priest would leave the child behind. She said it didn't always work, but they were united to protect each other.

A group of strong Native women raised me, including my mom and aunties. Women who were friends, cousins, and siblings, but always referred to each other as sisters. Native women with a long-shared history of uniting in order to protect their loved ones. The quick, adaptive behavior the women developed in these horrific boarding schools are gifts to my generation. Their experiences helped them teach us the right way. We stand up for ourselves, we ask outside communities to reconcile what has happened to our people and we are proud of where we have come from.

When the Colville Confederated Tribes took over St. Mary's in 1973, the school was closed and stayed shuttered for decades until it reopened as the Paschal Sherman Indian School. The private school reflects Colville Tribal heritage where Tribal traditions and practices are promoted, honored and embraced.

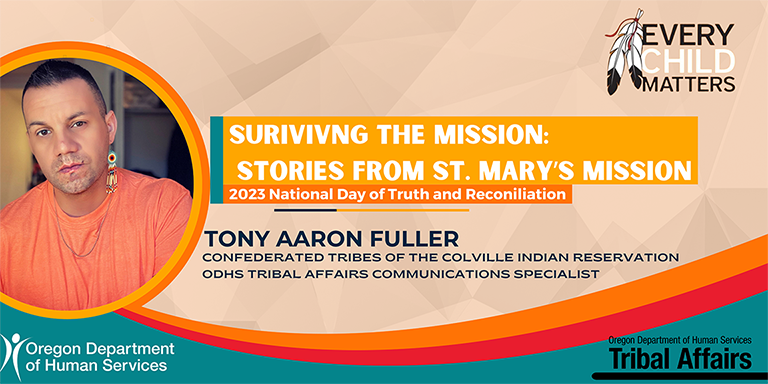

Tony Aaron Fuller - Enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation and the Tribal Affairs Communications Specialist with the Oregon Department of Human Services