Oregon's geology tells fantastic stories of awesome volcanic eruptions, cataclysmic floods and titanic continental collisions. To see the places where these events took place and to understand how they have shaped our landscape is a thought provoking and humbling experience. Over the years,

Oregon Geology magazine has featured these "Places to see" as signposts that point to our geologic past. Fantastic stories are waiting to be discovered! Take a

Geologic Field Trip

Newberry Crater National Volcanic Monument, south of Bend

The “crater” is, strictly speaking, a caldera—the remnant of a large shield volcano that collapsed during its eruptive life between about 500,000 and less than 2,000 years ago. With many eruptions continuing after the collapse, a great diversity of volcanic landforms and rock types was created here. This view to the south shows the central pumice cone that separates East and Paulina Lakes, with the Big Obsidian Flow stretching behind to the caldera rim.

Fort Rock State Monument, Lake County

Fort Rock with its steep rock sides is the most striking example of the maars and tuff rings in the young volcanic landscape of the High Lava Plains province. It was formed by a shattering explosion in early Pleistocene time, when rising magma met a shallow lake that covered the Fort Rock and Christmas valleys. The lake water eroded part of the crater ring and left wave-cut benches that can be seen especially near the tips of the horseshoe-shaped “fort.” In the caves cut along the edge of the lake in this vicinity, evidence of early human habitation has been found, including the 10,000-year-old woven sandals that are now thought to be the oldest shoes on record.

Photo contributed by Steve Fritz of Portland.

Moccasin Lake, Eagle Cap Wilderness, Wallowa Mountains

This tarn lake, filling an ice-gouged rock basin, lies in the center of the Wallowas at an elevation of nearly 7,500 ft. It is one of the many marks left from the carving done by Pleistocene ice, which covered a large portion of these “Oregon Alps.” Nine large glaciers radiated out from here during the ice age between two million and 10,000 years ago. The rock at the core of the Wallowa Mountains is the Wallowa batholith, granite from a magma upwelling in Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous time (between 160 million and 120 million years ago) that also cemented together a great diversity of still older, “exotic” terranes—blocks of the Earth’s crust that traversed the Pacific Ocean and attached themselves to the (then) edge of the North American continent.

Sand dunes at Honeyman State Park, Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area

Sand dunes that have formed since the end of the Ice Age occupy approximately 140 of Oregon’s 310 miles of coast; more than in Washington or California. The oldest dunes are not easily visible any more; they are perched on marine terraces or eroded or covered with vegetation. The post-Ice-Age dunes in the coast segment between Coos Bay and Sea Lion Point (just north of Florence) are the most spectacular parts of the National Recreation Area. This is the longest strip of dunes along the Oregon coast, extending for about 55 mi and mostly about 2 mi but in places up to 3 mi wide. The dunes can be as much as a mile long and nearly 500 ft high. The slipface, the steeper, leeward side of the pictured dune, shows marks of sand streams where the dune corrects its oversteepening slopes.

Photo courtesy of Oregon Department of Transportation.

Shore Acres State Park near Cape Arago in Coos County

A marine terrace borders the Coos County shore for much of the distance between the entrance to Coos Bay and the Curry County line. Rocks on which the terrace was formed differ along the shore, and erosion along this terrace has produced a shore with varied and magnificent scenery. Different degrees of resistance to erosion have allowed the waves to sculpture the terrace into sharp points of land, reefs, islands, secluded coves, and a myriad of smaller forms. Here, near Cape Arago, the terrace is on a sequence of Tertiary sedimentary rocks that are inclined steeply toward the east and cut by numerous fractures. Erosion has shaped a shore that is distinctly different from that of any other part of the Oregon coast. The predominant rock unit, the Coaledo Formation, contains an abundance of marine fossils. The park is also home to a famous formal garden and has, on the site of the former owner’s mansion, an observation building that is popular for spectacular views and whale watching.

Sheep Rock, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Grant County

Below a cap of erosion-resistant basalt, eroded channels lead down through 1,000 ft of ancient volcanic ash to the John Day River. This ash, now turned to claystone, contains the fossils of plants and animals from 25 million years ago.

Photo courtesy of National Park Service (negative no. 370).

Mitchell area, Wheeler County

The photograph, taken from a point near the junction of State Highway 207 with U.S. Highway 26 just west of Mitchell, offers a view to the southwest toward Bailey Butte in the foreground, White Butte behind it, and the north flank of the Ochoco Mountains in the background. Here we are on the southwestern edge of the Blue Mountains province and in a region whose underpinnings contain some of the oldest rocks and fossils of the state. These basement rocks are considered to be part of the Baker terrane—fragments of 250-million-year-old oceanic islands that wandered a long way across the ancestral Pacific Ocean before crunching into the North American landmass near the Oregon-Idaho border. Thus began the process that extended the continent farther and farther to the west and created most of the land on which we live today. Much of this area is underlain by Cretaceous marine sediments that were deposited in 100-million-year-old offshore basins The buttes seen in the photo mark the deeply eroded roots of 40- to 50-million-year-old volcanoes. Folding, faulting, continental volcanism, uplift, and erosion over the last 50 million years have combined to produce an extremely complex and interesting geologic province.

Photo contributed by Jamie Sands of Pendleton.

Lake Owyhee, Malheur County

Lake Owyhee, created by a dam on the Owyhee River, offers boaters an extraordinary view of Miocene volcanism (about 15 million years ago). Ash from that time preserved plant and animal fossils that show a much wetter climate. Rhinoceroses lived next to ancestral horses, deer and antelope. The off-white ash layers, pinkish-gray rhyolite, and dark colored basalt create a colorful palette. The Owyhee Uplands have been uplifted to more than 4,000 feet above sea level, and the resulting stream erosion has produced the deep, narrow, winding canyons seen in the area today. The Owyhee volcanic field includes several calderas, such as at Grassy Mountain and Mahogany Mountain, that are large collapse features better recognized by the distribution of specific types of volcanic rocks rather than by present day topography. These same volcanic processes have been responsible for numerous gold occurrences which have been prospecting targets over the last few years. Typically, the gold occurs as microscopic particles that have been deposited by hot-spring systems. Portland State University graduate students often learn geologic mapping in this area (several theses have been written and abstracts published in Oregon Geology).

Photo courtesy of Oregon Department of Transportation.

Kiger Gorge, Steens Mountain Recreation Lands, Harney County

Kiger Gorge is one of several glacial valleys on Steens Mountain in southeastern Oregon. It is here seen from the rim rock at the head of its broad, U-shaped valley. The U shape is typical of a valley carved by a glacier, while river valleys have a V shape. Glaciers advanced during the Pleistocene (less than 2 million years ago), when the climate was colder and wetter than today. At that time, the present-day Alvord Desert (15 mi to the southeast of Kiger Gorge) was part of lake that was 70 mi long and 12 mi wide.

Photo courtesy of Oregon Department of Transportation.

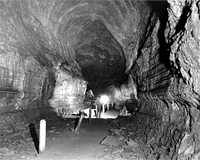

Lava River Cave, Newberry National Volcanic Monument

Lava River Cave, properly called a lava tube, whose side walls show the marks of the basalt lava that continued to flow, while its outside was cooling and turning into hard rock. Entrance to the tube became possible after a portion of its ceiling collapsed. The beginnings of the flow extend back to the nearby Newberry shield volcano which produced a great variety of volcanic attractions, including cinder cones, pumice cones, lava and obsidian flows, Lava Cast Forest, caves, lakes, streams, and waterfalls. Many of the Newberry basalt flows are less than 10,000 years old and retain the fragile surficial features that are characteristic of freshly erupted lava. The youngest ones have little or no vegetation and a stark moonscape appearance which was used for astronaut training in 1966. The whole area is now part of the Newberry National Volcanic Monument, managed by the USDA Forest Service.

Photo courtesy of Oregon Department of Transportation (photo no. 4177).